THE POETRY AND UTILITY OF TOM KUNDIG

Cabin standing on stilts, shuttered gliding rust steel, sliding reveals light…

A house: glass, concrete, steel: wheels crank open, flowing to the lake…

The staircase, a dragon /angles through the house /light, exit…

Tom Kundig’s structures resemble haiku: brief in their economy, utilizing the minimum and most immediate of materials to invoke resonance; they have zen capabilities—they bend in the wind, glisten (and rust) in the rain, illuminate with the snow… Haiku emphasizes the place of man or culture in relation to nature: in Kundig’s work, a natural syncopation occurs with the environment… And like the haiku, Kundig’s buildings possess enduring beauty:

‘There’s a tradition in Switzerland—in direct parallel, obviously things like a Swiss army knife—both beautiful and also functional. The beauty also helps the function of the thing. I always thought that Swiss design has a foot in both, first the function of the piece then the beauty of the piece came out of that function. You can see that thread in Zumthor’s work or Herzog and de Meuron. Celebrating that beauty and function is architecture for me.’

Kundig, who grew up in the Pacific Northwest, cites the vast, open natural and industrial landscapes of his childhood as an enduring influence:

‘The landscape probably had the biggest impact on me as a child. Also my parents were from Switzerland and we’d go back to Switzerland all the time—of course the Swiss environment is all about the mountains and the landscape so it’s kind of a natural connection…’

The milling and logging industries of Washington state, the mining structures, the coupling of forests and sawmills, the large farm machineries: this mechanical realm shaped the young Kundig’s understanding of the world. The other major influence of his youth was the sculptor Harold Balazs, who was a family friend:

‘His style of working influenced me— fabricating out of the landscape—there was clearly a reverence to the landscape; a fascination with the materials of industry, steel, concrete, large objects… There’s a sense of art and poetics I got from watching and working with him.’

This sensibility has emerged as a distinct feature of Kundig’s work: an ability to juxtapose the most basic of construction materials to conjure their innate beauty, within the context of time. Chicken Point Cabin, a weekend home in Northern Idaho, utilizes concrete block, steel, concrete floors and plywood—all left unfinished to naturally age and ‘and acquire a patina that fits in with the natural setting’.

The industrial landscapes of his youth also find their imprint here. “Gizmos” have become a familiar trait of Kundig’s work. These are mechanical feats of engineering —extremely sophisticated in conception and execution, but deceptively simple in appearance. Chicken Point Cabin’s centerpiece is a 30 ft. “window wall” which opens up on to the lake and surrounding woods. The six ton edifice of glass and steel is pivoted open with a hand-cranked wheel, easy enough for a six year old to manipulate (and he frequently does). Kundig and his engineering collaborator, Phil Turner came up with a system of gears (not unlike a bicycle) to create counter-balances to offset the weight.

These “gizmos” transform the houses into dynamic machines: creating a flow into surrounding nature or an alternate ebb of necessary boundaries —given the caprice of natural forces. In both cases, a sleight of hand: the structure is ‘at one’ with the environment.

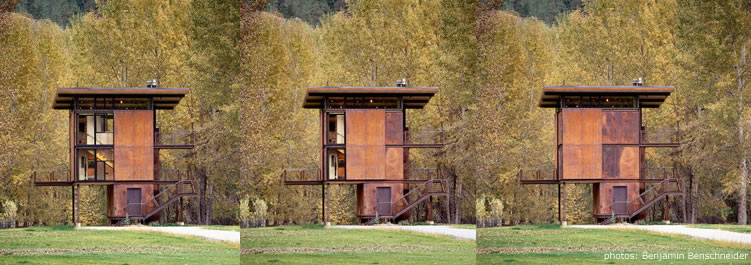

Another Kundig house, the award winning, “Delta Shelter” a 1000 square foot cabin built on stilts near a flood plain, features a similar hand-cranked device (though this involved a different set of engineering problems.) Giant steel shutters slide open, when the owners are in residence, and shut when they are away. The steel, in classic Kundig fashion, is allowed to interact with the elements and rust gracefully…

It is no wonder the architect has developed a reputation for his understanding of the ‘Great American Outdoors’—so what happens when he’s challenged with an urban setting?

‘The question is— that’s great! What about the cultural landscape? What about the city? I’ve been doing more and more work in the city, and I would say that there’s a parallel exploration of the city—very similar to natural setting: you’re trying to pick up the context of the place, and the context of it in the city and where the city is culturally and historically— and of course the function that the client had in mind. You have this stew and you put it together in this functional poetic way so that the architecture happens.’

Case-in-point: the new site of Sedgwick Rd, a Seattle-based advertising firm, was in a old machinery building. Kundig and his team took inventory of all the features slated for demolition: steel I-beams, first-growth wood beams, original wood doors and windows, aluminum light fixtures, a steel crane… They stored them until they figured out how they could rework them into the final design. The “patina” that Kundig often strives for evolved out of this marriage of the historical and the immediate.

But how to derive the same effect in an environment that is ‘off-kilter’…

‘It makes it more interesting, because then it sort of questions the whole place. Again, in an ideal world or an ideal setting (which there never is), there are discoveries that you make that are off-kilter or unresolved and those are the surprises. And they just need to hold it over poetics and make it more interesting because they raise issues that are their specialty and design.’

This is a serious consideration in architecture these days. Environmental issues have created new trends in design and fabrication— and a buzz word: “sustainability”. Kundig isn’t so impressed with the new frenzy:

‘Frankly that’s been an issue since the 60s. People have been talking about this for a long time—in fact even our ancestors had to deal with it on their own terms before we had piles of oil to exploit…’

Speaking of ancestors, Kundig did put quite a bit of thought into sustainability as a masters student in Seattle at the start of the 80s. His thesis focused on the Swiss Chalet as a sustainable structure—

‘They had to work with the environment— with what was available. They had to be very careful, insulate, do all these things to survive, and I think that’s really the bottom line about building a sustainable future…’

Again, the simplicity and the gift for working with materials and concepts already in place. The German artist Joseph Beuys once said: “All weather is good”. It’s the sort of koan that sums up the work and design philosophy of Tom Kundig.